Is it Time to Redesign Earth Day?

By Allison Arieff

Remembered for sparking federal environmental protection programs, the event was gradually co-opted by the very interests it was meant to oppose. In its 50th year, can we reimagine Earth Day?

This image of the earth was captured by the astronauts aboard the Apollo 17 spacecraft in 1972. Courtesy the U.S. National Archives

Below is a photo of one of the first houses in the United States to be heated by the sun’s energy. It was designed by Mária Telkes, a Hungarian chemist and biophysicist known to her colleagues at MIT as the Sun Queen for her work in solar research. The photo was taken in 1948.

When I look at it, I wonder why Earth Day—which celebrates its 50th anniversary on April 22—has not helped to instill a deeper ethos of ecological design in the United States. I see Telkes’s house as a model that could have become the standard, but never did. Had Levittown rolled out with solar panels, would there maybe have been a better chance?

Over the decades, Earth Day has, at best, inspired us to imagine something better, a new social compact if you will. But it’s an understatement to say its impact hasn’t been felt enough.

Mária Telkes, a solar researcher at MIT, developed the passive heating system for the Dover Sun House (1948), one of the first solar residences in the country. Telkes collaborated on the project with the architect Eleanor Raymond, a progressive builder in her own right. Courtesy Harvard Graduate School of Design; Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Read up on the origins at the Earth Day website and you’ll learn that in the decades leading to the first Earth Day in 1970, “Americans were consuming vast amounts of leaded gas through massive and inefficient automobiles. Industry belched out smoke and sludge with little fear of the consequences from either the law or bad press. Air pollution was commonly accepted as the smell of prosperity. Until this point, mainstream America remained largely oblivious to environmental concerns and how a polluted environment threatens human health.”

Over 20 million people took part that April day, engaging in symbolic rituals like dumping piles of trash on the steps of their local city halls or holding fake funerals for polluting automobiles. All standard-issue protest stuff, except that the very first Earth Day helped lead to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the Clean Air, Clean Water, and Endangered Species Acts (almost in the same year!), with Richard Nixon, a Republican, as president. In the ’70s, environmental action could still be a bipartisan effort.

The First Earth Day saw a mixture of teach-ins, rallies, and demonstrations across American cities and school campuses, including the University of Michigan (pictured here). Among the most colorful happenings were mock trials and burials for automobiles, which might be (uncharitably) described as a stunt. But the effects of Earth Day were, in fact, very real, leading to a series of federal laws to safeguard environmental resources and natural habitats. Courtesy University of Michigan School for the Environment and Sustainability/Creative Commons

Fast-forward to 2020: Since taking office, the Trump administration has rolled back 95 environmental rules and regulations. Climate plans in 2020, to the extent that there is anything resembling a U.S. climate plan, are designed to protect fossil fuels and corporate interests. In addition to a lack of bipartisan support for an environmental agenda, there are sharp divisions within the Democratic Party on what that agenda should even be. Even a return to the protection acts of the ’70s—or to the Paris Agreement— won’t cut it.

What is needed, and is desperately lacking, is imagination. Our ability to envision or design a better future seems not only constrained but derivative. Instead of Rick Guidice’s visionary renderings of space settlements or the inventiveness of Archigram and Bucky Fuller, we get a watered-down amalgam of all that in the designs of Bjarke Ingels, who is now developing a master plan for the Amazon rainforest with Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, a climate change denier, as a client. Ingels is also formulating a master plan for the entire globe. We’ve gone from Whole Earth to Master Planet. Is it too much to ask for creativity and integrity?

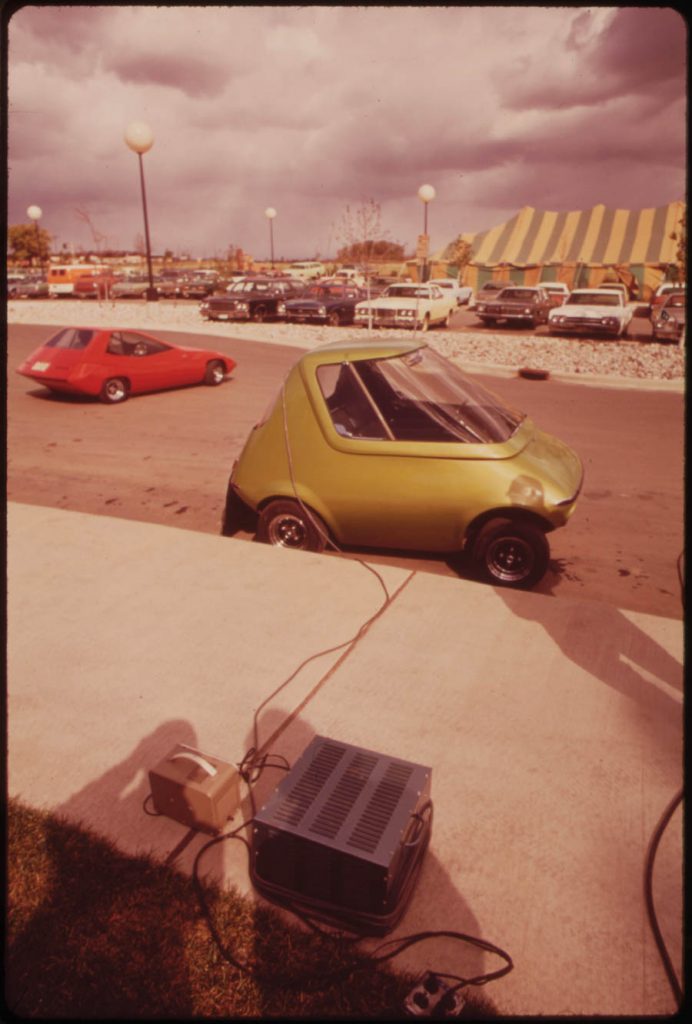

The automobile—and the oil industry it depended on—had become the poster image of pollution. And in light of the oil embargo of 1973, carmakers made forays into electric alternatives, as evidenced by events like the Exhibit at the First Symposium on Low Pollution Power Systems Development. Sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency and held in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in October of that year, the expo featured prototypes of all shapes and sizes, such as this one from GM. Courtesy The U.S. National Archives

Much of the stagnancy of the environmental movement can be attributed to a shift in emphasis from the collective to the individual. Earth Day too has followed this trajectory, inexplicably switching its focus in the 2000s from targeting corporations to building awareness of global warming. In doing so, it helped solidify the notion that fighting climate change is the responsibility of the individual—that solutions need not be systemic, but just a matter of changing our personal behavior. Earth Day, like the environmental movement writ large, has also been slow to recognize the importance of equity and inclusion, and has most often failed to acknowledge the disproportionate impacts of environmental injustice on the poor and people of color.

Earth Day hasn’t made us less addicted to our first-world habits. We’re commuting longer distances, walking less, and consuming more. The majority of homes built in the United States continue to increase in square footage, even as family size decreases. The neighborhoods where these homes are built typically have few to no connections to public transit, and many of them bear Walk Scores of zero. And only about 2 percent of those homes are being designed by architects. With few exceptions, the building industry is notoriously slow to innovate. Sustainability still very much feels like a “nice to have” in far too many projects.

If the Earth Day of 1970 fretted over the impacts of “massive and inefficient automobiles,” imagine what it would make of the Hummer, recently reintroduced as an electric car. Auto manufacturers (and car designers by extension) have abandoned even the once-ubiquitous sedan in favor of sport utility vehicles, which assert the right of the driver at the expense of pedestrian safety. Autonomous vehicles are hailed as the answer to our transportation future, yet reflect an inability to look past the car toward more sustainable ways of getting around.

Earth Day’s activist origins had, until only recently, receded into the past, overshadowed by corporate America’s takeover of the holiday. But a younger generation, inspired by the likes of Greta Thunberg, is once again taking to the streets. Courtesy Terry Ballard/Creative Commons

Architects and designers today have at their disposal a dizzying array of materials and technologies that allow them to be greener, but the already minimal incentives to make using them cost-efficient are getting smaller. So while yes, it’s true that a house in a neighborhood getting solar panels might inspire copycats, it’s also the case that encouraging that first homeowner typically requires some cajoling in the form of rebates or discounts. As we watch those offers disappear in this responsibility averse administration, advances in sustainability feel like one step forward, ten steps back.

Long ridiculed for bell-bottoms, free love, and harvest-gold appliances, the ’70s were actually an incredible period of discovery and invention in design. The era gave rise to the eco-exuberance of Ant Farm, Earthships, and eco-domes. Cars were cute and compact—the BMW 2002, the VW Bug—as were most houses. Furniture designers embraced organic shapes and natural materials. Residential interiors featured bold and earthy colors, eccentric juxtapositions, and macramé— not so much of the witness-protection program Modernism we see nowadays.

Am I nostalgic? A little bit. Because today, I’m struck by how limited our capacity to imagine a different reality has become. Our greatest minds (and dollars) are focused on socalled innovations that contribute to the diametric opposite of the original ideals of Earth Day. With all that brain power and capital, why are we left with flying taxis and internet-connected diapers? We can do better.

I’m not going to lie; on the cusp of Earth Day’s 50th, I’m feeling that its impact on design has been about net zero. But maybe it’s just having a midlife crisis. This is not to say that there aren’t inspiring efforts and accomplishments out there, from the Sunrise Movement to kids (including my own) participating in climate protests en masse to the passionate ideas of efforts like Project Drawdown and the Green New Deal.

Earth Day may have miscalculated by putting too much emphasis on the individual, but that doesn’t mean we should stop taking personal responsibility. It means we should recognize that we must find a way to rely on one another in order to find a way forward—and maybe Earth Day needs to switch back to taking corporations to task.

I just finished Weather, Jenny Offill’s most recent novel, which is centered on the idea of climate grief. She ends the book, half jokingly, with what she calls “the obligatory note of hope.” The hope Offill finds is rooted in collective action; it is, she writes, “the antidote to my dithering and despair.”

This feels right. Not one of us can individually combat what sometimes feels like anti–Earth Day every day. But collectively we can. By voting. By organizing. By ditching the SUV. By walking more. By finding inspiration in the bold acts of others. By recognizing how deeply young people feel this crisis, and finding encouragement in their passionate commitment to doing something about it. “The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop,” writes Paul Kingsnorth in Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto. “Together, we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us.”